- Home

- Philip Pullman

Count Karlstein Page 9

Count Karlstein Read online

Page 9

Oh, I’m not a fool, you know. I’m no cuckoo.

So—if the Princess had been here a little while ago, she couldn’t be far away now.

So—look for a Princess, and I might find a missing girl.

Or—look for the doctor, and I might find the Princess.

Or—look for the missing girl, and I might find the doctor.

Simple!

I finished my sausages and beer and set out. And blow me down if within the next five minutes I didn’t come across two scoundrels who had the same idea as I did.

Just in front of the village green there’s a big house that belongs to the Mayor. One of those handsome old places, all carved wood and big wide eaves, and what was more, there was a light in one of the windows. This light shone out into his front garden and lit up a bit of the house next door. Between the two houses there was a narrow little alley, and from where I was standing on the bridge, shivering and wondering whether it might be worth having a scout around over the other side of the river, I could see a movement down that alley.

It looked as if someone had just slipped into it, quietly—just the tail end of a movement, like that. There he is! I thought. That’s the doctor all right. So I went after him. But I kept quiet, all the same. I’ve got a police record now; if you’re a known criminal, even if it’s just a matter of missing britches, you’d better not get caught or else it’s the maximum sentence and no arguing. So I went very quietly—and it’s a good thing I did.

I got to the Mayor’s garden and I was about to turn in to the alley when I heard whispering. It was a still night—you couldn’t mistake it. And it wasn’t Cadaverezzi at all.

I lowered myself with great care behind a bush, and listened. What I heard was this:

The first bloke said, “I never saw such a fool in my life. All you had to do was hold on to her—you had her in your hand, and you let go!”

The second bloke said, “I’m sorry, Count Karlstein, sir, I deeply and truly and humbly beg your pardon, sir, but—” (then he sneezed)—“but someone tipped a mug of beer down my back, sir, and—” (another sneeze)—“and as I have already suffered one drowning today, sir, my mind was momentarily filled with panic at the thought of another one, and I let go of the girl purely in order to preserve my life—an instinctive reaction, your grace, purely instinctive, quite uncontrollable.”

So this was the oily-looking fellow from the Jolly Huntsman that the sensible-looking fellow had told me about! And the other one—he’d called him Count Karlstein! My ears were straining so hard to listen, they must have looked as if they were on tiptoe.

“We’ll have to get her back, Snivelwurst,” said the first bloke. “And, by the devil himself, if you have her in your hand again, you’d better not let her go, not even if an avalanche descends down your neck. D’you understand?”

“Oh, yes! Yes, indeed! Yes, your grace, that’s—” (sneeze)—“very plain indeed, my lord. But, begging your pardon, your grace—” (sneeze)—“we’ve got one of them back, haven’t we? So why, if you don’t mind my asking, do we need the second one back, if I may make so bold as to ask?”

“Because if I know anything about Zamiel, he won’t be satisfied with one. He’ll want a square meal, not a snack. One adult might do—but one small girl wouldn’t be enough. Of course, I could always leave you up there, Snivelwurst.”

“No! No! You wouldn’t! Oh, ha, ha, what a wit you are, your grace! Leave me—dear, dear, what a joke!”

“Well, if we don’t find her,” said Count Karlstein, “we’ll have to leave someone else up there.”

“May I suggest—” (sneeze)—“a certain young girl from the village here? The one I have in mind, sir, is she—” (sneeze)—“whom you lately employed as maid, Hildi Kelmar by name, sir.”

“Interfering wench. I dismissed her this afternoon. Where is she now?”

“In the Jolly Huntsman, your grace. If I am not mistaken, it was she who gave the alarm of fire in the parlor a little while back, to our great discomfiture, your grace.” (Sneeze.)

“A mischief-maker, eh? No one’ll miss her, then. Not a bad idea, Snivelwurst….”

Now, that little conversation might have meant nothing at all to a lot of people. It would even have meant nothing to the great Cadaverezzi, I have no doubt. But it meant a good deal to me, because I was brought up by the most fearful, superstitious old band of ninnies there ever was. I was an orphan, you see, and in the orphanage in Geneva there was an old woman called Maria Neumann, who was in charge of all of us young blisters that was there, and she couldn’t control us at all—poor old thing. We used to run riot. The only way she could make us do what we were told was by threatening us with the Demon Huntsman—the great and horrible Zamiel, the Prince of the Mountains, on his black horse, with his pack of luminous hounds and skeletons for his whippers-in. We shut up then all right. She used to smack her old lips together at the thought of us young ruffians being haunted by those frightful hounds—made our blood run cold. Even now it makes me shiver a bit; but then—under that bush, with two villains scheming some kind of devilry—to hear the name Zamiel gave me a proper turn.

Then the oily fellow sneezed sadly, and the count himself came out of the alley and set off down the road. He came within a foot of me, and I had a good look at him: a lean, wolfish, twitchy sort of individual, with a gnawing look about him—he might have been chewing the handle of his stick, now I come to think of it—and eyes with the white showing all round the pupil. Like his heart was being squeezed dry, making his eyes pop out. Disagreeable. I watched him stride off down the road, and then I got out of the bush and followed the oily-looking fellow. I hoped he’d go near the river, and he did—and I popped up by the bridge and beckoned to him.

“Shhh!” I said, putting my finger to my lips.

He crept up on tiptoe, like a stork in slippers. “What is it?” he said.

“Down there!” I whispered. “Shhh!”

“What?” He peered over the bridge.

“Down there in the shadows,” I whispered.

“What? What?”

“Someone moving—look—lean over a bit more—”

“I can’t see….”

So he leaned further out, and I tipped him in. Served him right. I let him yell and splash for a bit, and I yelled and roared as well to make him think he was drowning and being swept away, and then I went down the bank and hauled him out. He’d had a good soaking and he was starting to bubble a bit; and I laid him on a good sharp rock and knelt on him, to squeeze the water out, as I told him, and he yelled a good bit more, until windows opened and sleepy heads looked out and told us what they thought of it all. They knew some choice language, too.

“Did you see ’em?” I said.

“S-s-see who?” (Sneeze, sneeze, sneeze.)

“An Italian-looking feller and a little girl,” I said, “creeping along the bank. They looked like they was up to no good.”

“W-w-where did they go?” (Sneeze, sneeze.) “I m-m-must find them! E-m-m-mergency!” (Sneeze.)

I pointed—anywhere—and he was off, dripping and sneezing and squelching and shivering. Pathetic, of course; but I couldn’t help being a little afraid of whatever it was that could make a spindly little runt like him so neglectful of his own comfort as to run about on a winter’s night, still doing his master’s business, even after a soaking like that. It must have been pretty powerful; so instead of laughing at him, I felt—as I said—afraid.

Oh, yes, Max Grindoff’s not ashamed to admit it. I can be frightened sometimes. And I was more frightened than this before we’d finished.

However, I thought of what they’d said, those two, back in the alley—about the girl from the inn, Hildi, about how they’d give her to the Demon Huntsman instead of the Princess, if they couldn’t find her. So I thought: the Jolly Huntsman’s the next place for you, me boy—and about time too. A drop of brandy just now’d go down a treat.

That’ll do for the time being. I’ve got to

hand over to someone else now, so the young person can put down her pen and have a rest.

I had to face Ma first, of course. She wasn’t angry, which would have been bad enough, but hurt and sad, which was worse.

“Whatever did you do that for?” she said. “I was so looking forward to that little show, and you go and spoil it. I can’t understand you, Hildi. You’re as bad as Peter sometimes. I don’t know….”

And she sat down heavily by the kitchen table and mopped her eyes with her apron. She looked old suddenly, and tired, and overcome. There was nothing I could say to comfort her; and there was plenty of clearing up to be done. Old Conrad, the barman, was still in the bar, because one or two of the men who’d been in earlier were still up, swapping stories and boasts about their shooting, and there was a great litter of mugs and glasses and dirty plates that everyone else seemed to have forgotten. I felt exhausted, and worried, and friendless and hopeless and everything-else-less.

Then, just as I was setting off for the kitchen with an armful of plates and a handful of mugs, the door opened and in came Doctor Cadaverezzi’s servant, the one called Max. I looked at him in surprise, but what was more surprising was that he looked as if he expected to see me.

“Can I have a word, in private, like?” he said. Quietly, so the last fuddled drinkers in the bar shouldn’t hear.

“Come in the kitchen,” I said.

Ma had gone to bed. I put the plates and mugs down on the table and looked up to see him peering out of the back door.

“What are you doing?” I said. “There’s no one out there!”

“Can’t be too sure,” he said. “Are you going to wash the dishes?”

“If there’s any hot water,” I said.

“I’ll give you a hand. Let’s get all them plates out here and then we can talk, in private, like what I said. It’s important, else I wouldn’t ask.”

So we did. And when I’d looked in the copper to see if there was any hot water, and he’d ladled it out for me and refilled the copper from the well while I started to wash, he found a cloth and stood beside me in the candle-lit scullery and told me everything he knew. He worked well, too—quick and efficient and tidy. I liked him more and more. He stacked the plates properly and gave the knives and forks a good rub.

I listened without interrupting, and then I told him all I knew, and he listened without interrupting me. When I heard that Count Karlstein was planning to give me to Zamiel if he couldn’t find Lucy, I shivered with fear; but when I heard that he’d treated Snivelwurst just as I’d done, I laughed out loud.

“But what it all boils down to,” he said, when we’d finished and sat down by the fire, “is that we know where Miss Davenport is, and we think we know where Miss Charlotte is, but we don’t know where Miss Lucy is, or where Doctor Cadaverezzi is; and Miss Davenport doesn’t know where Miss Lucy is, and Doctor Cadaverezzi doesn’t know where I am, and neither of the girls knows that Miss Davenport’s here at all, or that Count Karlstein’s still prowling about somewhere in the village, and—”

“I’ve lost track,” I said. “We’ve got to find out if Charlotte’s escaped—that’s the main thing.”

“But why?” he said. “I thought you put the key in her soup. She must have got out by now.”

“But then Frau Muller found me in her parlor with the tray in my hand—they might have guessed what I was doing, and found the key! Or she might have been caught on the way out!”

“Hmm. Well, anyway, I reckon we ought to find Lucy first. I reckon that’s the most important thing. Because—”

“No, because at least she’s still free, so Count Karlstein hasn’t got her, has he? But Charlotte may be still in the tower. So we might have to get her out—”

“We’ll have to find Doctor Cadavarezzi—”

“We’ll have to keep clear of the count—”

“We’ll have to get into the castle—”

“We’ll have to look in the mountain guide’s hut—”

“We’ll have to see Miss Davenport,” we both said together. And we looked at each other across the old kitchen table, with the little candle burning low and the last ashes of the fire settling in the hearth, and reached out our hands and shook them solemnly.

“Now?” he said.

“Now,” I said.

I got my cloak and wrapped it around myself, and we left. The village was asleep by now; the only light came from the parlor window of the inn, and as I looked back even that wavered and died away. Old Conrad was closing the bar.

The walk up to the woodcutter’s hut took the best part of an hour. Max talked cheerfully at first, but even he couldn’t keep it up for long; and tiredness, and apprehension, too, soon got the better of me. In the end we trudged along in silence, with only the crunch of our footsteps in the snow and the occasional cry of an owl breaking the vast quiet of the forest.

When we were nearly there, I stopped and looked around carefully. There was a path that led off to the left, but you wouldn’t see it unless you knew where to look. I could see the flicker of a small fire as we shoved our way through the dense bushes and the snowy undergrowth, and then we were there.

But no one else was. The place was deserted.

“Where’s she gone?” said Max.

“They can’t have left very long ago or the fire would have gone out,” I said. “These logs are fresh—look, they haven’t been burning long.”

Max took a burning stick out of the fire and, holding it like a torch, put his head inside the hut.

“No one in there,” he said when he came out, “but all her things are there—that little cart of hers and her tent and so on—” He held the stick high and looked around.

And then, without any warning, a shot rang out from the trees, very close—so close I could see the flash of the powder at the same time as I heard the noise. And the stick Max was holding flew out of his hand and went spinning, like a firework, through the air behind him, and fell into the stream with a hiss. Then, in the ringing silence that followed, I heard very distinctly the sound of a little click. My brother, Peter, was a hunter; I’d heard guns since I was a baby, and I knew that sound well. It was the noise a hammer made, when it was raised to strike against the flint of a pistol. Whoever had fired the first shot was preparing to fire another; and he couldn’t have wished for better targets than Max and me.

One day, I have no doubt, it will be as common for young ladies to be instructed in the arts of making a fire, of catching wild animals, and of skinning and cooking them, as it now is for them to be taught to paint in watercolors and to warble foolish ditties while attempting to accompany themselves upon the pianoforte. They do both of these things very badly, in my experience. In my Academy in Cheltenham I did try to instill some sense of adventure and enterprise into my girls, but, I am afraid, with little success. Who can prevail against Fashion? And these days it is the fashion for young girls to pretend to be frail, to languish, to swoon, to utter little fluting cries of rapture when they are pleased, and to lose consciousness altogether when they are not. Anything more ridiculous than the spectacle of great stout red-faced girls of fifteen or sixteen attempting to be frail romantic heroines can scarcely be imagined. But they will do it; nothing will persuade them of how absurd they look; they will not be told otherwise, because it is the fashion. I wait, with such patience as I can muster, for the fashion, like the wind, to change and blow from another quarter. When that day comes, may Augusta Davenport be there still, to hail its dawning!

My maid Eliza is a case in point. Once her young man, Max Grindoff, had left us, I could see her become more nervous by the minute. It was quite instructive to watch—or it would have been, had I been able to see it. But darkness, of course, was necessary to the effect. Instead, I had to rely on her remarks.

—“Miss Davenport, do you believe in ghosts?”

—“Oh! Miss Davenport! I heard a spirit—I’m sure I did!”

—“Miss Davenport—did you see that horri

d dark form hastening between the trees?”

—“Oh, Miss Davenport! What a frightful sound!”

(An owl, of course; but she would not believe it.)

—“Miss Davenport! A bat—I declare! Oh! Oh! Do you think it is a vampire?”

—“Oh, listen! Miss Davenport, can you hear the wolves? I’m sure it is wolves—”

By the time we reached our destination, the girl was nearly insensible with fear. Not real fear, of course—she is good-hearted enough to stand up bravely to real danger, if any had threatened—but imaginary fear; fashionable fear. No sense in scoffing at her, of course; so when we reached the woodcutter’s hut, I set her to gathering some wood and lighting a fire while I explored a little way to see what I could discover about the lay of the land. Always a valuable exercise, this; once, in Turkestan, at the very edge of starvation, I surprised and shot a wild goat in just such circumstances. It was very tough, but it saved my life.

Nothing so nutritious showed itself this time, however, and I returned to the camp to find Eliza practically twittering with terror. I am afraid that I felt slightly impatient and I spoke sharply to her.

“Eliza, control yourself! Stop whimpering at me! Whatever is the matter with you?”

“Oh, Miss Davenport, I heard them, miss! There they were, the two of them, their poor little ghosts, drifting through the trees, miss!”

“What are you talking about?”

“The two little girls, miss!”

“Lucy and Charlotte? Are you sure?”

“They weren’t alive, miss! They were spirits! Phantoms! Driven through the night, unable to rest anywhere, because of a curse that follows them to the ends of the earth! And, miss—”

“What is it, girl?”

“One of them was carrying her head in her arms, miss….”

“What?”

The Golden Compass

The Golden Compass The Ruby in the Smoke

The Ruby in the Smoke I Was a Rat!

I Was a Rat! Once Upon a Time in the North

Once Upon a Time in the North The Tiger in the Well

The Tiger in the Well The Subtle Knife

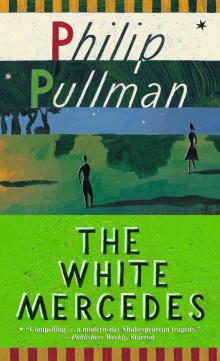

The Subtle Knife The Butterfly Tattoo

The Butterfly Tattoo Lyra's Oxford

Lyra's Oxford The Broken Bridge

The Broken Bridge The Amber Spyglass

The Amber Spyglass Count Karlstein

Count Karlstein The Scarecrow and His Servant

The Scarecrow and His Servant The Shadow in the North

The Shadow in the North The Collectors

The Collectors The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ

The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ La Belle Sauvage

La Belle Sauvage The Tin Princess

The Tin Princess The Firework-Maker's Daughter

The Firework-Maker's Daughter The Book of Dust: The Secret Commonwealth (Book of Dust, Volume 2)

The Book of Dust: The Secret Commonwealth (Book of Dust, Volume 2) Serpentine

Serpentine Daemon Voices

Daemon Voices The Amber Spyglass: His Dark Materials

The Amber Spyglass: His Dark Materials The Amber Spyglass hdm-3

The Amber Spyglass hdm-3 The Haunted Storm

The Haunted Storm The Golden Key

The Golden Key His Dark Materials 01 - The Golden Compass

His Dark Materials 01 - The Golden Compass Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm: A New English Version

Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm: A New English Version His Dark Materials 02 - The Subtle Knife

His Dark Materials 02 - The Subtle Knife Spring-Heeled Jack

Spring-Heeled Jack The Golden Compass hdm-1

The Golden Compass hdm-1 The Book of Dust, Volume 1

The Book of Dust, Volume 1 Two Crafty Criminals!

Two Crafty Criminals! Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm

Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm The Subtle Knife: His Dark Materials

The Subtle Knife: His Dark Materials His Dark Materials Omnibus

His Dark Materials Omnibus The Golden Compass: His Dark Materials

The Golden Compass: His Dark Materials The White Mercedes

The White Mercedes