- Home

- Philip Pullman

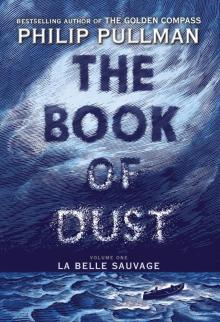

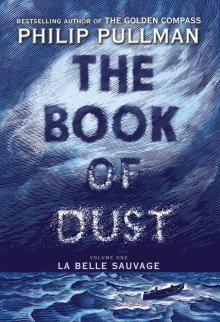

The Book of Dust, Volume 1

The Book of Dust, Volume 1 Read online

The Golden Compass

The Subtle Knife

The Amber Spyglass

Lyra’s Oxford

Once Upon a Time in the North

The Collectors (an e-story)

The Golden Compass Graphic Novel

The Ruby in the Smoke

The Shadow in the North

The Tiger in the Well

The Tin Princess

The Broken Bridge

The White Mercedes

Count Karlstein

I Was a Rat!

The Scarecrow and His Servant

Spring-Heeled Jack

Two Crafty Criminals

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2017 by Philip Pullman

Cover art and interior illustrations copyright © 2017 by Chris Wormell

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Visit us on the Web! GetUnderlined.com

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN 9780375815300 (trade) — ISBN 9780553510720 (lib. bdg.) — ebook ISBN 9780553510737

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v4.1

ep

World is crazier and more of it than we think,

Incorrigibly plural….

—Louis MacNeice, “Snow”

Contents

Cover

Other Titles

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter One: The Terrace Room

Chapter Two: The Acorn

Chapter Three: Lyra

Chapter Four: Uppsala

Chapter Five: The Scholar

Chapter Six: Glazing Sprigs

Chapter Seven: Too Soon

Chapter Eight: The League of St. Alexander

Chapter Nine: Counterclockwise

Chapter Ten: Lord Asriel

Chapter Eleven: Three Legs

Chapter Twelve: Alice Talks

Chapter Thirteen: The Bologna Instrument

Chapter Fourteen: Lady with Monkey

Chapter Fifteen: The Potting Shed

Chapter Sixteen: The Pharmacy

Chapter Seventeen: Pilgrims’ Tower

Chapter Eighteen: Lord Murderer

Chapter Nineteen: The Poacher

Chapter Twenty: The Sisters of Holy Obedience

Chapter Twenty-one: The Enchanted Island

Chapter Twenty-two: Resin

Chapter Twenty-three: Ancientry

Chapter Twenty-four: The Mausoleum

Chapter Twenty-five: A Quiet Rode

Three miles up the river Thames from the center of Oxford, some distance from where the great colleges of Jordan, Gabriel, Balliol, and two dozen others contended for mastery in the boat races, out where the city was only a collection of towers and spires in the distance over the misty levels of Port Meadow, there stood the Priory of Godstow, where the gentle nuns went about their holy business; and on the opposite bank from the priory there was an inn called the Trout.

The inn was an old stone-built rambling, comfortable sort of place. There was a terrace above the river, where peacocks (one called Norman and the other called Barry) stalked among the drinkers, helping themselves to snacks without the slightest hesitation and occasionally lifting their heads to utter ferocious and meaningless screams. There was a saloon bar where the gentry, if college scholars count as gentry, took their ale and smoked their pipes; there was a public bar where watermen and farm laborers sat by the fire or played darts, or stood at the bar gossiping, or arguing, or simply getting quietly drunk; there was a kitchen where the landlord’s wife cooked a great joint every day, with a complicated arrangement of wheels and chains turning a spit over an open fire; and there was a potboy called Malcolm Polstead.

Malcolm was the landlord’s son, an only child. He was eleven years old, with an inquisitive, kindly disposition, a stocky build, and ginger hair. He went to Ulvercote Elementary School a mile away, and he had friends enough, but he was happiest on his own, playing with his dæmon, Asta, in their canoe, on which Malcolm had painted the name LA BELLE SAUVAGE. A witty acquaintance thought it amusing to scrawl an S over the V, and Malcolm patiently painted it out three times before losing his temper and knocking the fool into the water, at which point they declared a truce.

Like every child of an innkeeper, Malcolm had to work around the tavern, washing dishes and glasses, carrying plates of food or tankards of beer, retrieving them when they were empty. He took the work for granted. The only annoyance in his life was a girl called Alice, who helped with washing the dishes. She was about sixteen, tall and skinny, with lank dark hair that she scraped back into an unflattering ponytail. Lines of self-discontent were already gathering on her forehead and around her mouth. She teased Malcolm from the day she arrived: “Who’s your girlfriend, Malcolm? En’t you got a girlfriend? Who was you out with last night? Did you kiss her? En’t you ever been kissed?”

He ignored that for a long time, but finally rat-formed Asta leapt at Alice’s scrawny jackdaw dæmon, knocking him into the washing-up water and then biting and biting the sodden creature till Alice screamed for pity. She complained bitterly to Malcolm’s mother, who said, “Serves you right. I got no sympathy for you. Keep your nasty mind to yourself.”

From then on she did. She and Malcolm took not the slightest notice of each other; he put the glasses on the draining board, she washed them, and he dried them and took them back to the bar without a word, without a glance, without a thought.

But he enjoyed the life of the inn. He especially enjoyed the conversations he overheard, whether they concerned the venal rascality of the River Board, the helpless idiocy of the government, or more philosophical matters, such as whether the stars were the same age as the earth.

Sometimes Malcolm became so interested in the latter sort of conversation that he’d rest his armful of empty glasses on the table and join in, but only after having listened intently. He was known to many of the scholars and other visitors, and was generously tipped, but becoming rich was never an aim of his; he took tips to be the generosity of providence, and came to think of himself as lucky, which did him no harm in later life. If he’d been the sort of boy who acquired a nickname, he would no doubt have been known as Professor, but he wasn’t that sort of boy. He was liked when noticed, but not noticed much, and that did him no harm either.

Malcolm’s other constituency lay just over the bridge outside the tavern, in the gray stone buildings set among green fields and neat orchards and kitchen gardens of the Priory of St. Rosamund. The nuns were largely self-sufficient, growing their vegetables and fruit, keeping their bees, sewing the elegant vestments they sold for keenly bargained gold, but from time to time there were errands a useful boy could run, or there was a ladder to be repaired under the supervision of Mr. Taphouse, the aged carpenter, or some fish to bring from Medley Pond a little way down the river. La Belle Sauvage was frequently employed in the service of the good nuns; more than once Malcolm had ferried Sister Benedicta to the R

oyal Mail zeppelin station with a precious parcel of stoles or copes or chasubles for the bishop of London, who seemed to wear his vestments very hard, for he got through them unusually quickly. Malcolm learned a lot on these leisurely voyages.

“How d’you make them parcels so neat, Sister Benedicta?” he said one day.

“Those parcels,” said Sister Benedicta.

“Those parcels. How d’you make ’em so neat?”

“Neatly, Malcolm.”

He didn’t mind; this was a sort of game they had.

“I thought ‘neat’ was all right,” he said.

“It depends on whether you want the idea of neatness to modify the act of tying the parcel, or the parcel itself, once tied.”

“Don’t mind, really,” said Malcolm. “I just want to know how you do ’em. Them.”

“Next time I have a parcel to tie, I promise I’ll show you,” said Sister Benedicta, and she did.

Malcolm admired the nuns for their neat ways in general, for the manner in which they laid their fruit trees in espaliers along the sunny wall of the orchard, for the charm with which their delicate voices combined in singing the offices of the Church, for their little kindnesses here and there to many people. He enjoyed the conversations he had with them about religious matters.

“In the Bible,” he said one day as he was helping elderly Sister Fenella in the lofty kitchen, “you know it says God created the world in six days?”

“That’s right,” said Sister Fenella, rolling some pastry.

“Well, how is it that there’s fossils and things that are millions of years old?”

“Ah, you see, days were much longer then,” said the good sister. “Have you cut up that rhubarb yet? Look, I’ll be finished before you will.”

“Why do we use this knife for rhubarb but not the old ones? The old ones are sharper.”

“Because of the oxalic acid,” said Sister Fenella, pressing the pastry into a baking tin. “Stainless steel is better with rhubarb. Pass me the sugar now.”

“Oxalic acid,” said Malcolm, liking the words very much. “What’s a chasuble, Sister?”

“It’s a kind of vestment. Priests wear them over their albs.”

“Why don’t you do sewing like the other sisters?”

Sister Fenella’s squirrel dæmon, sitting on the back of a nearby chair, uttered a meek “Tut-tut.”

“We all do what we’re good at,” said the nun. “I was never very good at embroidery—look at my great fat fingers!—but the other sisters think my pastry’s all right.”

“I like your pastry,” said Malcolm.

“Thank you, dear.”

“It’s almost as good as my mum’s. My mum’s is thicker than what yours is. I expect you roll it harder.”

“I expect I do.”

Nothing was wasted in the priory kitchen. The little pieces of pastry Sister Fenella had left after trimming her rhubarb pies were formed into clumsy crosses or fish shapes, or rolled around a few currants, then sprinkled with sugar and baked separately. They each had a religious meaning, but Sister Fenella (“My great fat fingers!”) wasn’t very good at making them look different from one another. Malcolm was better, but he had to wash his hands thoroughly first.

“Who eats these, Sister?” he said.

“Oh, they’re all eaten in the end. Sometimes a visitor likes something to nibble with their tea.”

The priory, situated as it was where the road crossed the river, was popular with travelers of all kinds, and the nuns often had visitors to stay. So did the Trout, of course, and there were usually two or three guests staying at the inn overnight whose breakfast Malcolm had to serve, but they were generally fishermen or commercials, as his father called them: traders in smokeleaf or hardware or agricultural machinery.

The guests at the priory were people from a higher class altogether: great lords and ladies, sometimes, bishops and lesser clergy, people of quality who didn’t have a connection with any of the colleges in the city and couldn’t expect hospitality there. Once there was a princess who stayed for six weeks, but Malcolm only saw her twice. She’d been sent there as a punishment. Her dæmon was a weasel who snarled at everyone.

Malcolm helped with these guests too: looked after their horses, cleaned their boots, took messages for them, and was occasionally tipped. All his money went into a tin walrus in his bedroom. You pressed its tail and it opened its mouth and you put the coin in between its tusks, one of which had been broken off and glued back on. Malcolm didn’t know how much money he had, but the walrus was heavy. He thought he might buy a gun once he had enough, but he didn’t think his father would allow him to, so that was something to wait for. In the meantime, he got used to the ways of travelers, both common and rare.

There was probably nowhere, he thought, where anyone could learn so much about the world as this little bend of the river, with the inn on one side and the priory on the other. He supposed that when he was grown up he’d help his father in the bar, and then take over the place when his parents grew too old to continue. He was fairly happy about that. It would be much better running the Trout than many other inns, because the great world came through, and scholars and people of consequence were often there to talk to. But what he’d really have liked to do was nothing like that. He’d have liked to be a scholar himself, maybe an astronomer or an experimental theologian, making discoveries about the deepest nature of things. To be a philosopher’s apprentice—now, that would be a fine thing. But there was little likelihood of that; Ulvercote Elementary School prepared its pupils for craftsmanship or clerking, at best, before passing them out into the world at fourteen, and as far as Malcolm knew, there were no openings in scholarship for a bright boy with a canoe.

—

One evening in the middle of winter, some visitors came to the Trout who were out of the usual kind. Three men arrived by anbaric car and went into the Terrace Room, which was the smallest of all the dining rooms in the inn and overlooked the terrace and the river and the priory beyond. It lay at the end of the corridor and wasn’t much used either in winter or summer, having small windows and no door out to the terrace, despite its name.

Malcolm had finished his meager homework (geometry) and wolfed down some roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, followed by a baked apple and custard, when his father called him to the bar.

“Go and see what those gents in the Terrace Room want,” he said. “Likely they’re foreign and don’t know about buying their drinks at the bar. Want to be waited on, I expect.”

Pleased by this novelty, Malcolm went down to the little room and found three gentlemen (he could tell their quality at a glance) all standing at the window and stooping to look out.

“Can I help you, gentlemen?” he said.

They turned at once. Two of them ordered claret, and the third wanted rum. When Malcolm came back with their drinks, they asked if they could get a dinner here, and if so, what the place had to offer.

“Roast beef, sir, and it’s very good. I know because I just had some.”

“Oh, le patron mange ici, eh?” said the oldest of the gentlemen as they drew up their chairs to the little table. His dæmon, a handsome black-and-white lemur, sat calmly on his shoulder.

“I live here, sir. The landlord’s my father,” said Malcolm. “And my mother’s the cook.”

“What’s your name?” asked the tallest and thinnest of the visitors, a scholarly-looking man with thick gray hair, whose dæmon was a greenfinch.

“Malcolm Polstead, sir.”

“What’s that place over the river, Malcolm?” said the third, a man with large dark eyes and a black mustache. His dæmon, whatever she was, lay curled up on the floor at his feet.

It was dark by then, of course, and all they could see on the other side of the river were the dimly lit stained-glass windows of the oratory and the light that always shone over the gatehouse.

“That’s the priory, sir. The sisters of the Order of St. Rosamund.”

“And who was St. Rosamund?”

“I never asked them about St. Rosamund. There’s a picture of her in the stained glass, though, sort of standing in a great big rose. I ’spect she’s named after it. I’ll have to ask Sister Benedicta.”

“Oh, you know them well, then?”

“I talk to ’em every day, sir, more or less. I do odd jobs around the priory, run errands, that sort of thing.”

“And do these nuns ever have visitors?” said the oldest man.

“Yes, sir, quite often. All sorts of people. Sir, I don’t want to interfere, but it’s ever so cold in here. Would you like me to light the fire? Unless you’d like to come in the saloon. It’s nice and warm in there.”

“No, we’ll stay here, thank you, Malcolm, but we’d certainly like a fire. Do light it.”

Malcolm struck a match, and the fire caught at once. His father was good at laying fires; Malcolm had often watched him. There were enough logs to last the evening, if these men wanted to stay.

“Lot of people in tonight?” said the dark-eyed man.

“I suppose there’d be a dozen or so, sir. About normal.”

“Good,” said the oldest man. “Well, bring us some of that roast beef.”

“Some soup to start with, sir? Spiced parsnip today.”

“Yes, why not? Soup all round, followed by your famous roast beef. And another bottle of this claret.”

Malcolm didn’t think the beef was really famous; that was just a way of talking. He left to get some cutlery and to place the order with his mother in the kitchen.

In his ear, Asta, in the form of a goldfinch, whispered, “They already knew about the nuns.”

“Then why were they asking?” Malcolm whispered back.

“They were testing us, to see if we told the truth.”

The Golden Compass

The Golden Compass The Ruby in the Smoke

The Ruby in the Smoke I Was a Rat!

I Was a Rat! Once Upon a Time in the North

Once Upon a Time in the North The Tiger in the Well

The Tiger in the Well The Subtle Knife

The Subtle Knife The Butterfly Tattoo

The Butterfly Tattoo Lyra's Oxford

Lyra's Oxford The Broken Bridge

The Broken Bridge The Amber Spyglass

The Amber Spyglass Count Karlstein

Count Karlstein The Scarecrow and His Servant

The Scarecrow and His Servant The Shadow in the North

The Shadow in the North The Collectors

The Collectors The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ

The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ La Belle Sauvage

La Belle Sauvage The Tin Princess

The Tin Princess The Firework-Maker's Daughter

The Firework-Maker's Daughter The Book of Dust: The Secret Commonwealth (Book of Dust, Volume 2)

The Book of Dust: The Secret Commonwealth (Book of Dust, Volume 2) Serpentine

Serpentine Daemon Voices

Daemon Voices The Amber Spyglass: His Dark Materials

The Amber Spyglass: His Dark Materials The Amber Spyglass hdm-3

The Amber Spyglass hdm-3 The Haunted Storm

The Haunted Storm The Golden Key

The Golden Key His Dark Materials 01 - The Golden Compass

His Dark Materials 01 - The Golden Compass Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm: A New English Version

Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm: A New English Version His Dark Materials 02 - The Subtle Knife

His Dark Materials 02 - The Subtle Knife Spring-Heeled Jack

Spring-Heeled Jack The Golden Compass hdm-1

The Golden Compass hdm-1 The Book of Dust, Volume 1

The Book of Dust, Volume 1 Two Crafty Criminals!

Two Crafty Criminals! Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm

Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm The Subtle Knife: His Dark Materials

The Subtle Knife: His Dark Materials His Dark Materials Omnibus

His Dark Materials Omnibus The Golden Compass: His Dark Materials

The Golden Compass: His Dark Materials The White Mercedes

The White Mercedes