- Home

- Philip Pullman

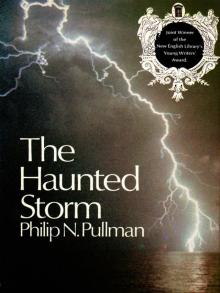

The Haunted Storm Page 3

The Haunted Storm Read online

Page 3

“I’ll tell you about when he met my parents. It was in May. My mother – oh she’s so secret and possessive and deathly proud about me! – wanted to meet him and she made me ask him to supper, though I didn’t want them to meet. But she insisted and when he came I’d just had a row with my father and we were all tense; and he hardly said a word until suddenly, out of the blue, he said to my father ‘I hear you’ve discovered a well.’ And it was just as if he knew it was the worst thing in the world he could have said, because the well is my father’s secret really and he was furious when it came out in the local paper about him – the well proves something important in his system of religion – oh God;” and she shivered as if with a great effort, “help me get to it.

“So we all went quiet. And my father said yes, he had, and what about it. And my lover said ‘l want it; that’s all.’ Just like that, as calm as you please; but I knew from his expression that he was – throwing acid in my father’s face; that’s what it came to. And my father went as white as a sheet and asked him in a sneering sort of way what he wanted it for. My head was spinning, but I had to side with my lover! I had to champion him! He wanted it for his party, he told me later, but I never found out why.

“And my father was getting frightened. He was so strong, my lover, so – implacable. It got worse and worse and then we were all talking together; my father got to his feet and then he started shouting and told him to go, and forbade me to see him again; but I ran out of the house and as I caught him up he was calm, so calm, and smiling gently – I was trembling, wild and upset – he smiled gently and told me where to meet him, and left without another word.”

While she said this the girl sat quite still, with her eyes closed and her face tense and stiff. Matthew left his hand where it was, with the knuckles pressed against her belly, and strained to listen. He was absorbed in it all to the point where he forgot even to ask “why? what’s the meaning of all this? who is she and who’s this lover of hers?”

And when she stopped for a moment and opened her eyes, he saw that there were tears in them. It wasn’t the rain, because the instant the eyelids opened and the dark eyes looked at his, they brimmed over with moisture that ran down her cheeks, running swiftly from rain-drop to rain drop where they lay on her skin. She smiled at the same moment, a brilliant and rueful smile that admitted everything, admitted the tears, admitted the openness of her body to him, and admitted the fact that the two of them had now, on this Plutonian shore, become united in a firm and dreamlike closeness.

As for him, he longed with all his soul to hold her close to him and to go much further than the conditions he’d accepted allowed; but he saw clearly that the whole encounter was based on extraordinary conditions, of the earth itself and of its atmosphere as much as anything else, and so he stayed where he was without moving.

But just beneath his hand there was the opening into her body, and he could, perhaps, let something of his love into her through his fingers. He pressed gently into her belly with his knuckles and ran his fingers along inside the elastic of her panties to loosen it; the thin nylon caught on a rough fingernail. At the same time he lifted his head and looked at the beach below. The men he had seen approaching were now – though, seemingly, at a vast distance – at the foot of the Spur, buffeted by the wind and busying themselves with ropes. He could hear snatches of shouting above the roar of the waves.

He turned back to the girl; and she, when his fingers reached their goal, smiled and laid her head on one side as if it were on his shoulder, and he could feel the tenderness and confidence of the gesture across the cold, rain-dashed air between them as if there was nothing there but a pillow.

He caressed her up and down until she was as soft as a cloud, with all his heart in the careful movement of his hand. After a minute she began to speak again.

“The next time I saw him it was in secret just outside the village; and he told me that he’d let my father keep the Well for a time and do the restoring for him. He trusted him to that extent, he said. I didn’t care; I was his to do anything with, his for ever and not my family’s any more. I wanted to live with him and work for him but he wouldn’t let me. It was his secret heart I coveted. It became a symbol like an eagle. Yes, and like matter, that started to withdraw itself from that moment on, taking itself out of me like a hasty lover before – oh, before anything had happened to me – it stole out of me by night and left me open and empty, while his secret heart circled above me like an eagle waiting; was it threatening, or did it protect me from something? I didn’t know, and I couldn’t reach it to ask.

“The importance of it grew and grew. I thought of it as having some kind of affinity with the laws of matter, with nature, and it possessed me so I could think of nothing else, nothing at all…”

She looked straight in front of her as she said that and caught her breath in a deep gasp as if he had hurt her suddenly. He pressed less hard and changed the direction of his caress, squeezing the flesh softly between his two fingers.

“You know – you know I said about the bottle that shook because he wanted it to? Well, that was – I think that was because I’d just said something stupid that made him angry, and instead of showing his anger himself he made something else shake and smash itself. It fell off the shelf and smashed. He didn’t move but I jumped and burst into tears hysterically because I was so frightened by him. Then another time when he was angry – it was on a bus, we’d got on together, and there was a drunkard sitting there who was shouting and upsetting an old lady beside him and my lover just sat down quietly and didn’t even look at him but suddenly I felt sick, and it came from him like a blow, a great wave of anger that made a silence – and he said nothing at all, but I could see the drunkard go pale and then I felt faint and weak from the force of it. And the seats themselves and the drunkard’s head and body went – transparent – faint – for a second as if they were fading like a ghost, and everybody fell still and shocked. That was all. No-one said a word but I knew it came from him and he could make things unsure of themselves enough to go faint and pale like that. So that’s why I thought that his own secret heart that I knew nothing of was so linked up with the laws of matter.”

One of the men below them had tied a rope around his waist and was wading into the surf at the foot of the Spur. The light in the wheelhouse of the boat was fainter, and occasionally it flickered. Apart from wondering briefly what they were thinking of doing, Matthew was hardly interested. The scene down there was merely a study for a land scape with figures, set perhaps on the shores of Lake Avernus, lit by the irregular corpse-light of the white spray and the lightning; a fine, mysterious, Cimmerian picture, but of no great concern to him anymore. All his interest was centred in the remote and sexual world he and the girl in habited. He had found the opening of her body and his hand lay over it with the tip of one finger inside her. This, and the pressure of the way he was sitting, had brought him nearly to orgasm; and their two souls faced each other passionately as their bodies sat apart and while the fast-running current of her voice held them still.

“I’ve picked up things in my arms and pressed them close to me and cradled them for hours, kissing them even, because I was so remote and lost, and this making-love-to things was a way of getting back to the world of matter; I’ve been blown about, open and empty, on cold plateaus, searching for him and his matter–dominating touch to bring me back; the touch of him that dominated matter and brought me back to what I craved was all I looked for and I never found it anywhere… In Tibet when they had magicians there, there was a rite they used to perform. The magician would go alone into a dark room with a corpse in it. Then he’d lie down on the body, mouth to mouth, and hold it tightly, and think of a magical spell and repeat it over and over again. After a while the body would begin to move; its eyes would open and get brighter, and it would look around, and move its limbs feebly, but he mustn’t let go or stop thinking of the spell. The corpse would get stronger and force itself up, and twi

st and turn trying to get away, but he must hold on or else it would kill him; it would leap up and down, dragging him with it with his lips fastened on its mouth, and then, slowly, its tongue would begin to stick out and touch his lips, and he had to open his mouth and let it enter – and then suddenly bite it off, and the corpse would collapse. And he’d keep the tongue and work magic with it. That’s what he was doing with me, but I had nothing like that tongue to give him. It’s as if he did it with the corpse of a dumb person and couldn’t find the tongue and went away, and the corpse wanders all over the world, with its borrowed life seeping away, looking for the touch that animated it.

“And one way of looking is to open myself to the world and – sex, to search that way for the touch that brought me into matter. I know that he’s probably evil, because of the knowledge of morality in his eyes. Not just good and bad, but absolute good and evil! I know he saw them! But I couldn’t tell the difference between them, and I don’t care, because they’re not the poles I move between. Worlds… interpenetrate and the direction I move might seem arbitrary to you but I’m pulled by the north pole of my world! And the poles of my world are matter and spirit and I have to wander through many worlds searching for the touch that’ll bring me back to matter again, to make me feel at all…

“Do you see?” She was crying now, her voice raised high over the wind. “That’s what I’m doing! I’m seeking his touch at the hands of strangers, yes, strangers! Letting them touch me – do you know how many men I’ve let do this? Eleven! And you’re the twelfth! “

Suddenly she gasped, and sat upright, and stared straight into his eyes. If either of them moved, the world would collapse like a house of cards. The tension between them dimmed the sound of the wind and the waves; and with a rush like water Matthew felt, almost physically, their two souls flood together and meet and blend, embracing and penetrating each other completely in the psychic field that had formed around them. He felt tears filling his eyes and love choking him; he felt weak in all his limbs and broken by a great blow on his heart.

But then – in an instant – she scrambled to her feet and dashed the rain from her eyes, and faced him like a tigress. He fell back.

She shouted something; it was almost a scream. He could make out nothing coherent in it. Then she turned and ran off into the darkness.

He put his hands to his head, trying to stay where he was and not run after her. The sailors on board the vessel had launched the dinghy and were struggling through the surf towards the shore, and, seeing this, the man with the rope had turned back along the Spur.

The spray still crashed high into the air over the boat. The light was fading from the surface of things and darkness advanced over the sea. Matthew lay back on the shingle and shut his eyes, trembling. The rain fell evenly over all his body. He was uplifted and enslaved by the same force, and the world was wide again, and the universe in flood.

Chapter 2

As she screamed she was conscious of a powerful impulse not to let him hear what it was that she was crying out; and the sound got lost in the air as a wordless shriek. How could she let him know? How dare she? As she stumbled away over the shingle she heard her breath rasping in her throat and before she could do anything about it she was torn by a burst of sobbing, and she flung herself to the ground and cried, with great gusts of tears shaking their way out of her into the flying darkness.

She could not say “You are the one,” she could not tell him, because the whole balance of her life was tilted against finding him. To come upon him so suddenly put her in a dangerous position from which she could only escape by trying to deny that he existed. Oh! Everything she had told him was true! And now this casual stranger – was he casual? Perhaps not; he seemed as intent as she was, and his eyes went as far as she would go, and further, into the darkness – had plunged her again into the whirlpool which generated, it seemed to her, the seeds and forms of everything she was not. So; was it love she felt? But what else could it be? Well, if it was, love was a cold thing, as sharp and in different as a flailing sword, and now it had cut her again.

She lay still and exhausted on the shingle. The darkness was complete at last, and the rain had settled into a steady beating rhythm. She shivered. She was soaked through and through. She wondered what was happening down there on the rock: had there been men there, rescuing a boat? It had flickered intermittently on the screen of the world like a scrap of dream, and she was no longer sure if it had happened at all. And where was he now?

No; that was ended. She had discovered him, but she had turned her back and gone away; she had told him, but she had done so in a scream that no-one would have understood; and now it must come to an end, and be forgotten.

She gradually became conscious of a sharp pain in her left leg, and eased it away from a stone that pressed against the shin. As she did so she felt suddenly cold, as if she had been sustained up to that moment by the warmth in his hand and fingers. She shivered again, tired out and empty. Had he thought she was beautiful? The thought came from nowhere and disappeared.

She sat up stiffly and leant her weight on her right arm. The wind blew her hair across her eyes for a second, and the wet strands of it slapped and stung her cheeks. The light had all gone; she could see only the obscure line of the horizon, and when she looked round, the dim shapes of the sandhills; but she saw more from memory than by the sight of her eyes. The rain dashed into her face and numbed her.

Now she would have to leave this stormy mask behind her, and walk out of the drama of night and air and water and go back home, faceless. Tattered snatches of movement still caught at the edges of her soul and tempted her to run back down the beach, seek him out, force his eyes to stare into hers again and then never leave him; but they were only broken impulses without any weight of meaning behind them, and they clung for a second, and then fell off. The knowledge that in an hour or so she would have no identity – that she had no identity now – frightened her suddenly, but it was a familiar fear, and she knew how to deal with it.

Her method was to recollect as painstakingly as possible all the circumstances which had formed her, and then to pretend that they were true; to repeat her name over and over under her breath, and then to pretend that she was herself. In this way she preserved a fragile and tenuous stability which enabled her to live her real life and experience her real obsessions unobserved.

But this time, she realised, the reconstruction of her false self would have to be far more elaborate, detailed, and passionately carried out than ever before; because she had no way of telling when, if ever, she would be able to abandon it again.

She stood up carefully and leant against the wind, pushing her hair out of her eyes and looking intently towards the sea; and saw nothing there but chaos and darkness. A slight dizziness affected her for a moment, and she nearly fell over; and in that second she felt suddenly warm, and heard a voice speaking with great clarity; but when she recovered and stood upright again, she had forgotten what it had said.

She turned her back on the sea and began to walk up towards the dunes. She had so much to examine, to sort out – really, it seemed as if she had lived for a thousand years. She was assailed, as her feet met the first patch of sand, by an oceanic sense of tragedy that made her put her hands to her head and rock back and forth with anguish; and it was only after a low moan of pain had escaped her lips that she recognised the source of it in the intense pain in her ears, caused by the cold wind and the rain. The impressions of her senses and the impulses of her mind were inextricably confused; she realised it, and found in it merely another cause for regret. The world – and to the vague and unsatisfactory term “the world” she attached, in her own speculations, a precise, elaborate, and meticulously organised meaning – was retreating from her with the formal inevitability of a mass of high waters after a flood; and this was the only true cause of ruin, and the only true reason for anguish.

With her hands pressed tightly to the sides of her head she trudged up

the slope and into the dunes, where the going was heavy on the deep, soaking sand but where, at least, the force of the wind was broken and dispersed. Something in her chaotic state seemed to have improved a little: it was caused, she realised, by the simple dogged action of walking, which went a little way towards imposing a measure of order on the confusion of memories and emotions and movements that she was trying, now, to organise into a recognizable semblance of herself. Gradually the whirl of ideas began to find one or two vortices to settle around. She found herself wondering why, first of all, she had instinctively reacted as she had done towards the stranger, and why she had justified it to herself so emphatically afterwards; for now, a little calmer, a little less oppressed, she began to recognise in this refusal a cause of great potential sorrow. And secondly she began to take stock of herself once more: her head was less painful now, and as the rain seemed to be easing off, she took her hands away from her ears and brushed her hair back, pressing the water out as much as possible. She shook her coat, shivering with distaste as drops of moisture on the collar ran down her neck. Well, she had not drowned, nor had she been raped; so for the time being, she thought, her body was safe enough.

Half unconsciously she began to divide up the scattered pieces of sensation and knowledge that moved along with her into what was hers and what belonged to the night and the wind and the rain. And one of the first things she made herself acknowledge – with an involuntary smile – as she came out of the sandhills and into the grassy field, and saw the lights of the town in the distance, was the fact that her name was Elizabeth Cole.

The Golden Compass

The Golden Compass The Ruby in the Smoke

The Ruby in the Smoke I Was a Rat!

I Was a Rat! Once Upon a Time in the North

Once Upon a Time in the North The Tiger in the Well

The Tiger in the Well The Subtle Knife

The Subtle Knife The Butterfly Tattoo

The Butterfly Tattoo Lyra's Oxford

Lyra's Oxford The Broken Bridge

The Broken Bridge The Amber Spyglass

The Amber Spyglass Count Karlstein

Count Karlstein The Scarecrow and His Servant

The Scarecrow and His Servant The Shadow in the North

The Shadow in the North The Collectors

The Collectors The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ

The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ La Belle Sauvage

La Belle Sauvage The Tin Princess

The Tin Princess The Firework-Maker's Daughter

The Firework-Maker's Daughter The Book of Dust: The Secret Commonwealth (Book of Dust, Volume 2)

The Book of Dust: The Secret Commonwealth (Book of Dust, Volume 2) Serpentine

Serpentine Daemon Voices

Daemon Voices The Amber Spyglass: His Dark Materials

The Amber Spyglass: His Dark Materials The Amber Spyglass hdm-3

The Amber Spyglass hdm-3 The Haunted Storm

The Haunted Storm The Golden Key

The Golden Key His Dark Materials 01 - The Golden Compass

His Dark Materials 01 - The Golden Compass Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm: A New English Version

Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm: A New English Version His Dark Materials 02 - The Subtle Knife

His Dark Materials 02 - The Subtle Knife Spring-Heeled Jack

Spring-Heeled Jack The Golden Compass hdm-1

The Golden Compass hdm-1 The Book of Dust, Volume 1

The Book of Dust, Volume 1 Two Crafty Criminals!

Two Crafty Criminals! Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm

Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm The Subtle Knife: His Dark Materials

The Subtle Knife: His Dark Materials His Dark Materials Omnibus

His Dark Materials Omnibus The Golden Compass: His Dark Materials

The Golden Compass: His Dark Materials The White Mercedes

The White Mercedes