- Home

- Philip Pullman

Daemon Voices Page 13

Daemon Voices Read online

Page 13

To conclude: a writer’s intention with regard to a book is a complicated and elusive matter, and explaining each case truthfully and in full is not always possible. Would a reader want to know that complicated and elusive truth in any case? Would it be any use to them? Possibly, if they were genuinely interested in the process of composition, and prepared for ambiguities and contradictions and uncertainties; probably not, if their desire was for a simple answer that would end their anxiety about whether they’d really understood what the book was saying.

But it would be frivolous to maintain that a writer’s intention doesn’t matter at all. In other spheres of activity it matters a great deal. If we accidentally dislodge a flowerpot from a sixth-floor balcony on to somebody’s head, it’s unfortunate; if we intend to do so, it’s murder. The courts certainly recognise the difference. There is also the related question of responsibility. If a writer produces a story that has the effect of inflaming (for example) racial hatred, can he or she disclaim responsibility by saying that whatever intention they had, it wasn’t that, and that in any case their intention is irrelevant? To disclaim intention and responsibility altogether seems to me to regard the author as little more than an elaborate piece of voice-recognition software, taking down dictation from an unseen source. Of course our intentions matter to some extent: it’s just rather difficult to say what they are.

In practice, the way we answer questions depends as always on what we judge to be the needs, the age, the maturity and the intellectual ability of the questioner, and the situation in which the question is posed. If we’re lucky enough to have a long line of young customers waiting for us to sign their newly purchased books, we can’t spend much time on any of our answers; with a small group of well-prepared university students in a seminar room, the case is different.

But I think that I would try—that I do try—to explain that what I intended to do was make up as good a story as I could invent, and write it as well as I could manage. And I try to explain something about the democratic nature of reading. I say that whatever my intention might have been when I wrote the book, the meaning doesn’t consist only of my intention. The meaning is what emerges from the interaction between the words I put on the page and the readers’ own minds as they read them. If they’re puzzled, the best thing to do is talk about the book with someone else who’s read it, and let meanings emerge from the conversation, democratically. I’m willing to take part in such conversations, because I too have read the book, and if I’m asked about my intentions, then any answer I give will be part of the conversation too; but it’s hard to persuade readers that my reading has no more final authority than theirs.

In that way, I may not clarify much for people who want to know about my intentions, but I do introduce the idea of reader response theory, which is probably more helpful.

THIS ESSAY WAS FIRST PUBLISHED IN KEY WORDS IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE, EDITED BY PHILIP NELL AND LISSA PAUL (NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2011).

Beginning in 1986 I was lucky enough to work for a while at Westminster College, which is now part of Oxford Brookes University, with a man called Gordon Dennis. I learned a great deal from him, including the notion that you could say interesting things about children’s books just as much as you could about books that only adults would want to read. The growth of children’s literature as an academic subject is something I welcome warmly, despite the fact that I feel rather shifty about my own ability to talk academically, as I explain in the essay that follows.

Children’s Literature Without Borders

STORIES SHOULDN’T NEED PASSPORTS

On storytelling, children and adults

This talk is going to be partly at least about children’s literature, or so it says in the programme. I should say at the outset that I’m not going to treat the subject in an academic way, even if I could; I find it hard to think about anything for very long, or at all deeply, unless I can get some practical grasp of it. My qualifications for saying anything about books that children read are strictly limited to the fact that I write them. So these reflections are those of someone who makes up stories and thinks about how he does it, rather than those of a scholar who has studied the subject from an academic point of view.

I thought I should begin by trying to say what children’s literature is; but that’s not as easy as it seems. We think we know what it is—there are books about it, you can be a professor of it—but it still seems to me rather a slippery term. It’s not quite like any other category of literature.

For example, if we go into a large bookshop we find many different ways of dividing up the stock. We find books separated by genre, for example horror, crime, science fiction; but children’s books—children’s literature—isn’t a genre in that sense.

However, we also find shelves labelled women’s literature, black literature, gay and lesbian literature. Is children’s literature like that?

No, it isn’t like that either, because books of those kinds are written by members of the named groups as well as being about them and for them. After all, those categories, those bookshelf labels, came into being because people felt they needed a voice, not just an ear. They didn’t say, “Write more stuff for us!” They said, “We are writing, and we want to be read.”

But children’s literature isn’t produced by children. It’s written, edited, designed, published, printed, marketed, publicised, sold, reviewed, read, taught at every level from nursery school to post-graduate, and very often bought by adults. A novel written by a child is a very rare thing. Whereas we accept the idea of the child prodigy in the fields of music or chess or mathematics, those activities depend on abstract pattern-recognition more than on the sort of stuff that novels are made of, namely experience of life. A ten-year-old child writing something like A Dance to the Music of Time, say, or Pride and Prejudice, or Tom’s Midnight Garden, would be not a prodigy but a monster.

I’m talking about novels, not poetry: poems, at least to the extent to which they are patterns themselves, seem to be more within the reach of a young mind, and we’ve seen remarkable poems produced by young children under the guidance of good teachers such as Jill Pirrie (author of On Common Ground: A Programme for Teaching Poetry, Hodder, 1987)—though when I was teaching young children I was occasionally reminded of that observation by the pre-Socratic philosopher Ion of Chios: “Luck,” he said, “which is very different from art, sometimes produces things which are like it.” I’m perpetually conscious of the part that luck plays in my own work; it would be odd if it played no part in the work of others. We need to give children plenty of opportunity to be lucky.

So children’s literature isn’t like women’s literature or black literature; but there’s another difference as well. Membership in those other groups I mentioned is presumably a permanent condition: I have always been male, and white, and heterosexual, and while we can never be completely sure what’ll happen tomorrow, I’m fairly safe in saying that I always will be. But I was once a child, and so were all the other adults who produce children’s literature; and those who read it—the children—will one day be adults. So surely there isn’t a complete and unbridgeable gap between them, the children, and us, the grown-ups; or between their books and ours. There must be some sort of continuity here; surely we should all be interested in books for every age, since our experience includes them all.

Or so you’d think. But it doesn’t seem to work like that. To look at the reception of children’s literature today, you’d think that it was a separate thing entirely, almost a separate country, because there are important people like literary editors and critics, who decide what should go where, and why. People who act like guards on an important frontier, and who walk up and down very importantly carrying their lists and inspecting papers and sorting things out. You go there—you stay here. There was an example recently in the Times Literary Supplement. An eminent critic and poet was reviewing a novel tha

t appeared on its publisher’s adult list. The critic called it “too simple by a mile,” placed much of it on the abysmal level of Kipling’s Thy Servant a Dog, said, “The glossary of Australian slang terms is over-literal and out-of-date,” and laid into it heartily for being sentimental.

However, he added, “as a children’s book, it might make its mark.”

So children’s books, apparently, are like bad books for grown-ups. If you write a book that isn’t very good, we’ll put it over there, among the stuff that children read.

That’s not a view that’s unique to this country, and nor is it confined to the books themselves. Their authors are not very good either. A year or two ago I saw a piece by Robert Stone in the New York Review of Books. He was writing about Philip Roth’s latest novel. Stone opened by praising Roth for his great achievements in the past thirty years, the authority of his voice, his energy, his manic but modulated virtuosity, and so forth. Then he went on to say that Roth was—these are his words—“an author so serious he makes most of his contemporaries seem like children’s writers.”

Well, that put me in my place. You can imagine how embarrassed I felt at not being serious, and having a voice with no authority, not to mention a virtuosity that was sober and unmodulated.

The model of growth that seems to lie behind that attitude—the idea that such critics have of what it’s like to grow up—must be a linear one; they must think that we grow up by moving along a sort of timeline, like a monkey climbing a stick. It makes more sense to me to think of the movement from childhood to adulthood not as a movement along but as a movement outwards, to include more things. C. S. Lewis, who when he wasn’t writing novels had some very sensible things to say about books and reading, made the same point when he said in his essay “On Three Ways of Writing for Children”: “I now like hock, which I am sure I should not have liked as a child. But I still like lemon-squash. I call this growth or development because I have been enriched: where I formerly had only one pleasure, I now have two.”

But the guards on the border won’t have any of that. They are very fierce and stern. They strut up and down with a fine contempt, curling their lips and consulting their clipboards and snapping out orders. They’ve got a lot to do, because at the moment this is an area of great international tension. These days a lot of adults are talking about children’s books. Sometimes they do so in order to deplore the fact that so many other adults are reading them, and are obviously becoming infantilised, because of course children’s books—I quote from a recent article in the Independent—“cannot hope to come close to truths about moral, sexual, social or political” matters. Whereas in even the “flimsiest of science fiction or the nastiest of horror stories…there is an understanding of complex human psychologies,” “there is no such psychological understanding in children’s novels,” and furthermore “there are nice clean white lines painted between the good guys and the evil ones” (wrote Jonathan Myerson in the Independent, 14 November 2001).

Consequently any adult reading such stuff is running away from reality, and should feel profoundly ashamed.

In the same week, however, we had a well-known journalist and social commentator saying that children’s books are worth reading, because: “People are desperate for stories…Yet in our postmodern, deconstructed, too-clever-by-half culture, narrative is despised and a cracking read is as hard to find as a moth in the dark” (Melanie Phillips, Sunday Times, 11 November 2001).

So there’s a lot of tension along this border—a lot of pride and suspicion and harsh words and dangerous incidents. It might flare up at any minute, we feel.

But when we step away from the border post, when we go round the back of the guards and look about us, we see something rather odd. The guards have entirely failed to notice that all around them people are walking happily across this border in both directions. You’d think there wasn’t a border there at all. Adults are happily reading children’s books; and what’s more, children are reading adults’ books. A thirteen-year-old boy of my acquaintance was a passionate reader of Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Unconsoled; and only the other day I spoke to some children in the public library in Oxford, none of them older than thirteen, and found that they were reading, among other things, Dorothy L. Sayers, Agatha Christie, Ruth Rendell, Ian Rankin, Stephen King, David Eddings, Helen Fielding—much of it genre fiction, to be sure, but all of it firmly on the adult side of the border.

And I well remember my own childhood reading consisting among other things of Aldous Huxley and Lawrence Durrell as well as Superman and Batman, Arthur Ransome and Tove Jansson at the same time as Joseph Conrad and P. G. Wodehouse, Captain Pugwash overlapping with James Bond—a whole mixture of things, both apparently grown-up and apparently not. Furthermore, a book that made a great impression on me and my young schoolfriends was Lady Chatterley’s Lover. So highly did we think of its qualities that we used to pass it around from hand to hand; in fact, like many copies of that book, it used to fall open at the passages most keenly admired.

Now it’s quite common to criticise this kind of cross-border reading on the grounds that it’s reading for the wrong reasons. Adults today are reading Harry Potter, apparently, in order to be in the fashion, or to retreat into a state of childish irresponsibility; the teacher who confiscated our copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover did so because he thought it wasn’t the literature we were after, but the sociology. At least, I think that’s what he said; he said it in Welsh.

Reading for the wrong reasons is something that the guards on the border never do, but which other people do all the time, unless they’re supervised. Well, my view about that is that even if there are right and wrong reasons for reading, I don’t know what they are when I’m doing it, never mind anybody else. What’s more, it’s none of my business, and to make it still harder, everything is more complicated than we think. An ignoble reason for doing something can turn into a worthy one; as well as being intrigued by the sociology that was going on in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, I do remember being fascinated by the way Lawrence put words together.

This sort of mixing-up happens all the time, and in other fields as well as literature. One minute we’re admiring the way Degas puts his pastel marks on the paper, the next we’re wondering what it might be like to kiss the model. But then we notice something intriguing in the diagonals of the composition, and that sets us thinking about the Japanese print in the painting by Van Gogh on the other wall of the gallery, and while we’re thinking about Japanese art we remember that very sociological woodblock print involving the fisherman’s wife and the octopus; and that reminds us that it’s time for lunch. But on the way out, we look again at Degas, and think that his way with pastel really is exquisite. He puts this colour against that one, and something quite different happens. Could I do that with words? we think. How would it work?

And so on. Which are the wrong reasons there, and which are the right ones? They’re all mixed up together inextricably. And no one else can possibly know whether to condemn us for the ignoble, or praise us for the worthy. So I don’t believe for a second in criticising anyone for reading for the wrong reasons. We’re much better off minding our own business.

In a similar way, I don’t think it makes any sense for someone else to decide who should read this book or that. How can they possibly know? Much better not to decide at all, and just let things happen. One of the questions I’m addressing this evening is that of what children’s and adult literature have got in common: one thing they have in common, plainly, is that both literatures, whatever they are, are read by both groups, whatever they are. But as I began by saying, I’m thinking in a practical way of what will help me write; and one thing that helps me do that is the vision of a marketplace.

I like to imagine the literary marketplace as if it were precisely that, a place where a market is being held, a busy open space with a lot of people buying and selling, and eating and drinking,

and stopping for a gossip, and walking through on their way to somewhere else, or just running up and down and playing; and in this corner there’s someone playing the fiddle, and over there is a juggler, and here’s a storyteller on his square of carpet with his hat in front of him, telling a story.

And some people have gathered to listen.

They’ve got heavy shopping bags in their hands, and they probably can’t stay for long, but still, they’re intrigued, they want to know what’s going to happen next, so they stay a minute more, and then another, just to see how it turns out; and there’s an old man leaning on a stick, and here’s a child sucking a lollipop, and they’re both listening hard; faces looking over shoulders or peering between taller bodies, pressed together, crammed close, all listening. And some other people go past and listen for a moment and decide it’s not for them, so they go on somewhere else; and others walk past entirely oblivious, chatting together without noticing the story at all; and once in a while someone who has to leave and catch a bus sees a friend and says, “There’s a good story going on over there, you ought to go and listen.”

The Golden Compass

The Golden Compass The Ruby in the Smoke

The Ruby in the Smoke I Was a Rat!

I Was a Rat! Once Upon a Time in the North

Once Upon a Time in the North The Tiger in the Well

The Tiger in the Well The Subtle Knife

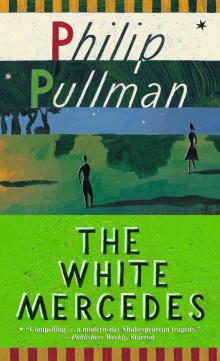

The Subtle Knife The Butterfly Tattoo

The Butterfly Tattoo Lyra's Oxford

Lyra's Oxford The Broken Bridge

The Broken Bridge The Amber Spyglass

The Amber Spyglass Count Karlstein

Count Karlstein The Scarecrow and His Servant

The Scarecrow and His Servant The Shadow in the North

The Shadow in the North The Collectors

The Collectors The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ

The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ La Belle Sauvage

La Belle Sauvage The Tin Princess

The Tin Princess The Firework-Maker's Daughter

The Firework-Maker's Daughter The Book of Dust: The Secret Commonwealth (Book of Dust, Volume 2)

The Book of Dust: The Secret Commonwealth (Book of Dust, Volume 2) Serpentine

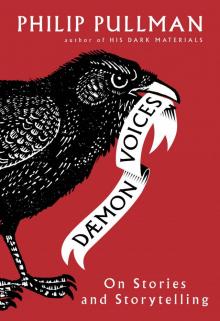

Serpentine Daemon Voices

Daemon Voices The Amber Spyglass: His Dark Materials

The Amber Spyglass: His Dark Materials The Amber Spyglass hdm-3

The Amber Spyglass hdm-3 The Haunted Storm

The Haunted Storm The Golden Key

The Golden Key His Dark Materials 01 - The Golden Compass

His Dark Materials 01 - The Golden Compass Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm: A New English Version

Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm: A New English Version His Dark Materials 02 - The Subtle Knife

His Dark Materials 02 - The Subtle Knife Spring-Heeled Jack

Spring-Heeled Jack The Golden Compass hdm-1

The Golden Compass hdm-1 The Book of Dust, Volume 1

The Book of Dust, Volume 1 Two Crafty Criminals!

Two Crafty Criminals! Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm

Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm The Subtle Knife: His Dark Materials

The Subtle Knife: His Dark Materials His Dark Materials Omnibus

His Dark Materials Omnibus The Golden Compass: His Dark Materials

The Golden Compass: His Dark Materials The White Mercedes

The White Mercedes